It [the cosmos] has come to be; for it is visible and touchable and has body, and all such things are sensed; and things that are sensed... came to light as coming to be and begotten. And again, for what comes to be, we claim that it's necessary that it come to be by some cause...

One must go back again and investigate the following about the all [about everything that exists]: to which of the two models the builder looked when he fashioned it--to the one that's in a self-same condition and consistent, or to the one that has come to be. Now if this cosmos here is beautiful and its craftsman good, then it's plain that he was looking to the one that's everlasting, but if otherwise--which isn't even right for anyone to say--then to the one that has come to be. Now it's clear to everyone that it was to the everlasting; for the cosmos is the most beautiful of things born and its craftsman the best of causes. Now since that's how it has come to be, then it has been crafted with reference to that which is grasped by reason and prudence and is in a self-same condition...

There's every necessity that this cosmos here be the likeness of something... So then, when it comes to a likeness and its model, one must determine how the accounts are also akin to those very things of which the accounts are interpreters. Now accounts of what's abiding and unshakable and manifest with the aid of the intellect are themselves abiding and unchanging; and to the extent that it's possible and fitting for accounts to be irrefutable and invincible, they must not fall short of this.

But as for accounts of something made as a likeness of something else--since it is a likeness--it is fitting that they, in proportion to their objects, be likenesses: just as Being is to Becoming, so is truth to trust (Timaeus 28B-29C)...

Since this is so, it must be agreed that: one kind is the form, which is in a self-same condition--unbegotten and imperishable, neither receiving into itself anything else from anywhere else nor itself going anywhere into anything else, invisible and in all other ways unsensed--that which is intellection's lot to look upon (Timaeus 52A)..."

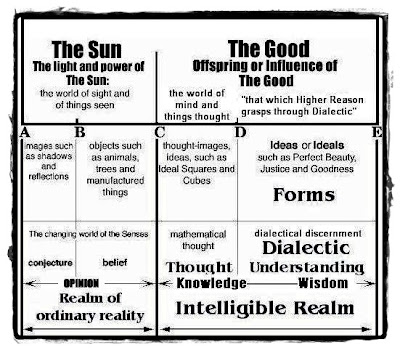

These forms are one of Plato's most popular ideas, implying that thoughts themselves exist on their own, in a more-perfect plane. I have summarized it this way before:

Here, in Timaeus, we can understand that Plato's theory of cosmological genesis happened temporally. The creator/poet/father took the perfect essences/ideas/forms which he knew and created something [literally] sensational from them. But, somehow in becoming sensational, the forms lost their purity, becoming imperfect and temporal instead of eternal.

In this way, what is rational becomes empirical. Aristotle, Plato's pupil, came to the opposite view.

Still, Plato believes that the forms exist, they are the things that our reason uses to tell objects apart. And, fittingly, there are objects that can only be in the formal world as well as objects that can only be in the sensational realm:

Many have used the Cave as an example of seeing the world unenlightened by the Good and other forms.

Here's Aristotle's view.

Here's Aristotle's view.

And, more of the Timaeus:

No comments:

Post a Comment